The National Theatre’s Romeo & Juliet directed by Simon Godwin with cinematographer by Tim Sidell, airs on Sky Arts 4 April 2021…this is a recent article in The Times, quite literally a ‘meeting of two worlds’…

TIM SIDELL // CV // WEBSITE

National Theatre’s Romeo and Juliet — a meeting of two worlds

Josh O’Connor and Jessie Buckley have filmed Romeo and Juliet in an empty National Theatre. It’s been a magical marriage of stage and screen, they tell Sarah Crompton

A huge white disc of a painted moon hangs on wires from gantries. To one side is a piece of scenery, a ledge with a railing, propped up so it seems to be floating in space. A French window frame, painted white, leads oC the balcony to a hint of a panelled room, with a grey scenery flat behind. As I watch, a figure in a pale pink suit emerges from the shadows and excitedly drags a ladder across to the balcony, where a woman crouches, waiting. They talk so softly that even if you are standing feet away, you can barely hear what they say, but as he tips his lanky frame over the balcony in his attempt to kiss her, you catch their mood of giddy joy. Banks of monitors show their actions in close-up; cameras catch every gesture. “Awesome,” the director Simon Godwin says. This is how the most famous love scene in the English language was filmed as part of a remarkable experiment in storytelling, a version of Romeo and Juliet that is a deliberate hybrid of film and theatre, made in 17 days on the closed stage of the National Theatre’s Lyttelton space. When all other theatrical activity had to shut down for the December lockdown, filming carried on in an otherwise empty building. The resulting 90-minute film will be shown on Sky Arts on April 4. |

“What’s been so amazing is that these two worlds — the National Theatre and its crew, and this incredible crew from film — have met for the first time,” says Jessie Buckley, who is playing Juliet. “We have felt we are creating something so particular, that catches the spirit of this moment against the odds.” Her Romeo, Josh O’Connor, grins and adds: “Everyone’s taken a risk. It was a question of, ‘Give us four weeks’ rehearsal and a director of photography and just trust us. We’ll make something.’ Which is basically what we did. If it hadn’t been for lockdown, there’s no way anyone would have let us do that. So that’s magic. We are discovering new things, exploring something that feels like it hasn’t been done before.” This version of Romeo and Juliet, originally slated for summer 2020, arose from a network of friendships. Godwin, the associate director of the National Theatre, had known O’Connor since he left Bristol Old Vic drama school. O’Connor has been friends with Buckley from around the same time. “We were going to set up a commune in Whitstable,” Buckley says, laughing. “We’re both country people so we wanted to get out of London.” |

“We were going to buy one of those buildings on stilts by the sea,” O’Connor adds, “have everybody live there. Make film, theatre. We might still.” Since then O’Connor has gone on to find worldwide fame as Prince Charles in The Crown, while Buckley has won attention with roles in films such as Wild Rose and Judy and the multi-award-winning Chernobyl on TV. When they signed up for the play, it was a dream come true; both longed to work in a building that has such a history in its bones. “Seeing all those shows that have been there,” O’Connor says. “I was even excited about going to the canteen.” They had got as far as walking on to the Olivier stage and seeing how it felt. “We were both bricking it,” O’Connor says, smiling. “That theatre’s huge and daunting.” “But exciting as well,” Buckley adds. Then Covid-19 hit, and a stage production became a film, created according to Covid-safe protocols. Both actors hope their version of Romeo and Juliet might eventually reach the stage. “Every now and then we do have moments of thinking it would be lush if we were on stage in the Olivier,” O’Connor says. “Because on the other side of the irons [stage curtain], there’s this empty auditorium and it is this weird looming feeling that never goes away. It’s not a film studio, it’s a theatre. It feels like a constant murmur.” |

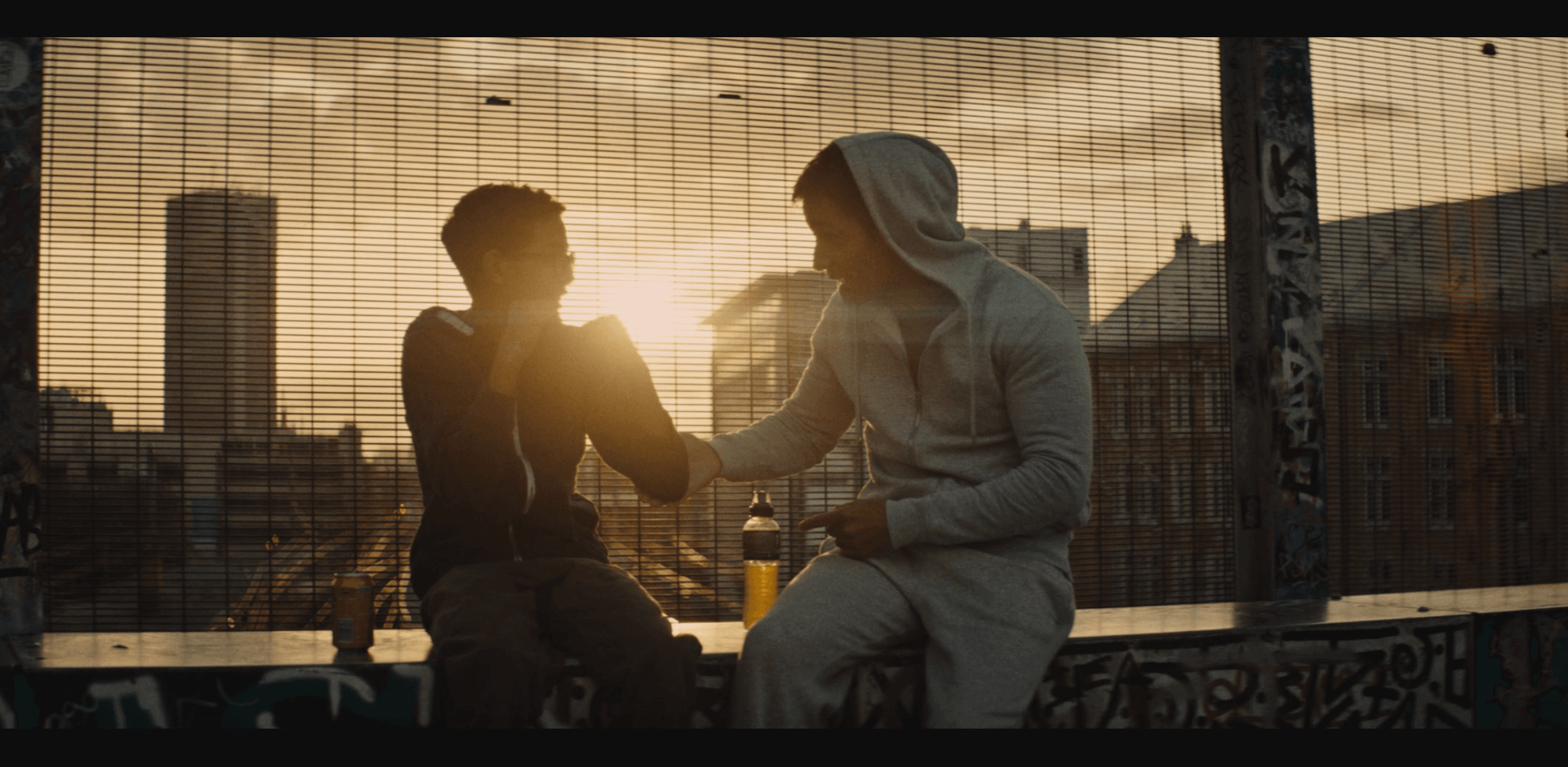

The Lyttelton stage was transformed into a black box for filming by closing the iron curtain and bringing in the back and side stages, which triple its size. Godwin, David Sabel, who had launched NT Live and is an independent producer, and the director of photography, Tim Sidell, whose credits include I Hate Suzie, hammered out a way of working that blended the National’s theatrical resources with expertise from the film world. “I was immediately struck by the intensity and the depth of the discussion and how everyone had their say, which is not quite the same in film,” Sidell says. “The answer to all my questions to the NT was always yes. It is such a new combination of theatre and film, and I love the way it spans both.” The balcony scene’s design was a case in point. Sidell was thinking of ways to create the sense of a moon in “a knowingly artificial way” and mentioned it to his gaffer, who mentioned it to the NT lighting team. Two days later someone found the moon in one of the props cupboards. “It was too good to be true, so we went for it.” |

This collaborative process was accompanied by a steep learning curve for Godwin who had flown in from Washington DC, where he is artistic director of the Shakespeare Theatre Company. He had never made a film, and daily rehearsals were preceded by “film school”, where Sidell taught him the basic grammar. He had to adapt to the diCerences between the two forms. “In theatre everyone complains about not having enough time, but really you’ve got ample time. You can carry on changing things through previews. This is walk in, do it, see it back, think you’ve missed a lot,” he says, with a grin. “I can see I am learning to swim while swimming the Channel. But there’s something empowering about it.” The clear advantage is that the detail he finds in his meticulous rehearsals can be expressed in close-up. “When I was working with Ralph Fiennes on the NT production of Antony and Cleopatra, he would often say to me, ‘Can we just do the cinema version’, and I wouldn’t know what he meant. But now I understand. It’s whispered, forensic, emotionally available, with no compromise for the fact that in the theatre you have to project to the back of the Olivier. That access to the intimate life of the characters is thrilling.” The key decision Godwin and the adaptor Emily Burns took was that the film would move from scenes shot in a rehearsal room to a more fully theatrical incarnation, changing at the moment Romeo meets Juliet at the Capulet ball. Instead of creating Verona on a film set, it asks the audience to suspend its disbelief as it would in a theatre. “It’s a question of believing the audience at home is capable of going on the same imaginative journey with us, but through a screen,” Burns explains. Godwin adds: “It also works with the way we are approaching the play: is love a kind of madness or a kind of truth, and where does authenticity lie in a world of overt imagery and theatricality?” | ||

For him, the root of the experiment was the chemistry between Buckley and O’Connor. “Their mutual aCection, respect, curiosity, shared sensibility.” That, at 30, they are older than is now usual for the star-cross’d lovers, was in O’Connor’s view an advantage.

“If you think the reason they are willing to die for each other is because they are young and naive, that to me is the biggest problem of the play. I don’t believe that. I can believe they are willing to die for each other because they f***ing love each other. Let’s play what love is, what that means.”

Buckley agrees. “The age thing doesn’t bother me. I think love is love, and this play is about needing to love instead of hate. Whatever age you are, love sends you completely crazy and reduces you to a very vulnerable state.”

Both are full of pride at the film and hope it will reach the widest audience possible. “What made me really excited,” Buckley says, “was that this space was dead and, through a story of love and with love of something we do, we made it alive again. Everyone was so happy to work. There was a real will to make something for the people who will come back to the theatre, to the empty stalls.”

Romeo and Juliet, Sky Arts, April 4